Parole Officer No. 2: Minnie Barton and the Crusade for Lost Women

There is something dark and gloomy about the little slip of Griffith Park that surrounds Fern Dell Drive. Once a village of the Native American Gabrielino tribe , the area is green and tan. Indigenous stones are landscaped to create a canal for a trickling river and paths for hikers heading up towards brighter trails and the gleaming Observatory high on the mountain. There is one lonely pile of tagged, terraced stones to the right of the road where there are picnic tables and two child-sized water fountains. Between the fountains-one works and one is dry- there is a plaque placed by the women's rights organization Soroptimist International in memory of one of its favorite members, a forgotten hero of Los Angeles who would have gotten that fountain fixed come hell or high water.

The First Crusade

"Rehabilitation is not yet a popular idea among many people who still think punishment and utter defeat is the only end of crime. I have always felt that answer lies much deeper than that."--Minnie Barton, L.A. Times December 1, 1940

Minnie Barton was born in Kansas in 1881. By 1905 she was a mother of three boys, living with her husband John in boom-town Los Angeles. L.A. was still a rough place with a wild west atmosphere, filled with lost women with no families or education, who often turned to prostitution or addiction to get by. Minnie, friendly and curious by nature, started visiting jails and police courts and observed that after these women were arrested and released from jail, there was no one to care for them. So, thoroughly-middle-class Minnie started befriending these disenfranchised women -- even those who reeked of liquor -- and she helped them, often bringing them into her own home without any formal permission from the authorities.

Her work was quickly recognized, and Minnie was offered a job at the LAPD as its only female parole officer (and only the second female on the entire LAPD force at the time). It was a position without precedence, and therefore, without pay. On February 7, 1906, Minnie reported to the rag tag city jail to find that there was no office set up for her, just an old stool taken in a recent Chinatown raid. Finally, the city jailer went to the basement and found her a desk and Minnie went to work. It was a demanding, even dangerous, occupation. Once, she was bitten by an inmate in court after she was denied bail. Minnie continued this work, without pay, for ten years.

As the city continued to grow and her case load continued to heave, Minnie realized more needed to be done. Her boys were growing older and she no longer felt comfortable having parolees in her home. She recounted a particularly humorous incident, when one of her inebriated charges was assumed to be her husband's girlfriend while they transported her on a streetcar. Minnie wanted a place for these unwanted women to feel safe and secure, where they could learn life and job skills until they got on their feet. What Minnie was envisioning was a halfway home -- and since she herself had just recently started receiving a salary from LAPD (along with the title Parole Officer No. 2), she knew it would be an uphill climb to raise any funds.

I'll let Minnie explain it herself:

I knew we had to have a place to send these girls and women in order to get them away from criminal influences. When I put this matter before the city council the answer was 'you are trying to reform those women. The problem is not ours -- it belongs to the churches.' But an invitation to discuss things brought only four people. Then I got the names of [women's] club presidents, stated my questionnaire to them, and the next meeting was so big we couldn't get them all in the room. The clubwomen have been helping ever since.--L.A. Times, March 10, 1940

Women's Clubs were an active and vital part of society in the first half of the 20th century. They were made up of civically minded, educated women. There was a club for everyone -- the Women's Advertising Club, the Mother's Pedology Club, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the Badger Club to name a few. Here women could collectively debate and pool resources to enact social change. They were also fond of speakers, with the clubs serving almost as continuing education courses (L.A. journalist Alma Whitiker wrote: "Though I am a good feminist and have high respect for women's clubs, their passion for speeches make me sigh!"). Minnie was a popular speaker and not above using shock value to raise funds. She once read aloud to the Women's Club of Los Angeles a particularly inappropriate letter one of her charges had received from a potential employer to illustrate what the less fortunate were up against.

In 1917, Minnie started The Big Sister's League in Los Angeles to help her make her halfway home a reality. She quickly obtained a lot at 2118 Trinity Street in the residential neighborhood of West Adams at a steep discount, and began construction on the Minnie Barton Home. Using donated materials and volunteer labor -- the mayor put in his time, Judge Fredrickson hoed weeds -- a two story structure was erected.

Minnie explained how she furnished the project:

Our interior decorating and scheme of furnishing were without precedent" Barton said with a grin. "We'd find a bedstead in one attic and the mattress in another, a chair here, curtains there, bully one woman into giving us her old linen and silver and another into buying new china so we could have her old. We certainly proved that every little bit added to what you've got makes a little bit more -- but we got it furnished.--L.A. Times, December 1, 1940

The Minnie Barton Home opened in July, 1918. The home was immediately filled with 15-20 women at a time, who stayed anywhere from under a month to two years. The women were taught to sew, can fruit, and perform housework. To raise funds for themselves and the home the women sold handmade goods in temporary stores downtown and hosted ham dinners for local dignitaries and women's clubs.

Judge Georgia Bullock, Minnie's great ally at the women's court, released many women to Minnie's custody at the house, as did the police department. They were not all parolees; some were simply women with nowhere to go. At various times the house took in a drug addicted nurse who beat a pensioner; Theo Carew, the former Broadway star turned Italian countess who ended up a vagrant after suffering brain injuries during shelling in WWI; an amnesia victim with a southern accent; and a woman who shot her gas station attendant lover after he refused to marry her. And then there were the Bigelow twins: two mentally-challenged ladies who became permanent fixtures at Minnie's homes.

The Feminist

"My heart goes out in sympathy to all women who make mistakes and to wives left helpless by conscienceless husbands, but I advocated the whipping post for such men-and I would not hesitate to assist personally in administering justice"--Minnie Barton, L.A. Times, December 1, 1940

It was not just those in trouble with the law or those with mental problems who needed help. Minnie quickly recognized the great plight of unwed mothers. During the 1920s the Los Angeles population was exploding, as dreamers from all over the country came in search of oil riches and movie glory. Many of these women ended up pregnant, penniless, and deserted with little government support. The Minnie Barton Home was the only aid agency in L.A. that took children, and they often had to turn mothers away due to overcrowding.

So funds were again raised, and the Bide-A-Wee Home for deserted mothers was built at 1315 Pleasant Avenue in Boyle Heights. Opened in 1923, the campus had 16 bungalows and an employment bureau and offered child care assistance. Many of the women gave the children up for adoption, and mothers who didn't were required to work and pay nominal rent if they were able, after their personal expenses were met. The actress Gloria Swanson slowly paid off the mortgage and the cycle of ham dinners and good's sales continued to pay for the rest.

Children were still allowed at the Minnie Barton Home as well. In 1924, a young British woman ran away from the home, leaving a toddler and infant behind. The toddler was claimed by the woman's "husband," but he refused the baby, a sickly little girl, insisting she was not his. So the women at the home claimed the child as their own and named her Minnie Barton Jr.

Long before the Christian Children's Fund or those Sarah McLaughlin SPCA commercials, little Minnie Jr. became a visual "mascot" of her namesakes' movement. Minnie Sr. again proved to be a genius in public relations, holding large birthday parties for the girl at Bide-A-Wee where the press was invited to tour the facilities, donate toys, and witness Minnie Jr.'s flourishing good looks and intellect. Minnie Sr. and her husband eventually adopted the child and brought her into their family.

The Fighter

"The women of the United States have waked up to the fact that it is up to them to right things. Just look at all the things that are being done for men and boys in this city, and all the money that is being spent by the city and by social agencies. Compare that with the little that is being done for girls and women who get into jail, are put on probation, are deserted by their husbands and have no one to care for them, or for that pitiful older group of women who nobody wants. When you think of their problems, you realize that it is up to us women to take care of them."--Minnie Barton, L.A. Times, March 10, 1940

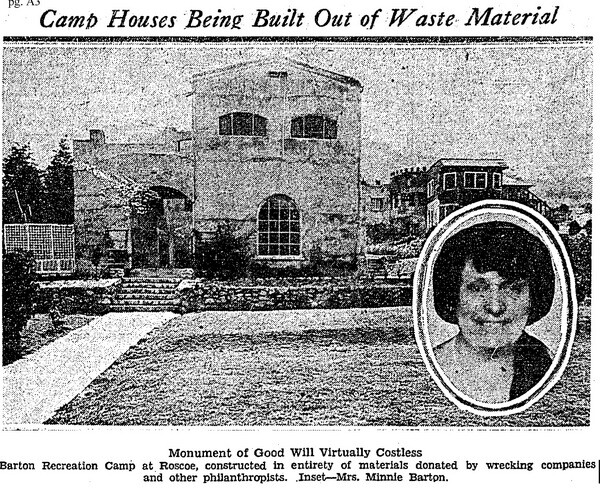

Minnie Barton was no sap. Her biggest brawl began in 1929, when she personally purchased land deep in the valley at 102225 Johanna Street, in the sparsely populated neighborhood of Hansen Heights (now Sunland). Together with the Big Sisters Club, she began construction on the Minnie Barton Recreation Camp, to help house the overflow of women needing assistance.

But the folks of Hansen Heights, led by L.A. pioneer Joseph Messmer, vehemently opposed the construction project. In June, an angry delegation threatened an injunction suit and told a police commission that unsavory characters helping with construction had climbed over fences and begged for food, which Minnie denied. When the commission found in Minnie's favor, a councilman proposed a resolution to make the area a single family residence zone -- expressly to force Barton out. The school superintendent was also brought on board, asserting that the camp was a menace to neighborhood children, and construction temporarily halted.

The protest continued in September when construction resumed, with allegations of drunken workers, lack of permits, and most disturbingly -- graft. Messmer charged that police vehicles, prisoners, and city materials were being used at the site. The commission again found in Minnnie's favor. In January 1930, Messmer was back at it, and Minnie had had it. She stated that she already had 24 women at the site, and that she had so many requests for assistance and so little government support that she didn't know what to do. After her speech the commission applauded her efforts and the project continued.

Finale

As the 1930s progressed, Minnie became more and more outspoken. Now considered the most popular speaker in L.A., she kept her job as parole officer while running her various philanthropic homes and dealing with personal adversity. In 1935, Minnie was involved in a serious car crash when a truck plowed into her police car. A year later her son Jack, a new husband and father, died of a rare heart ailment.

The '30s also brought new social challenges, as the Depression created a whole new group of displaced persons. Entire indigent families were now arriving in L.A. and were often pointed Minnie's way. The Depression also created an underclass of destitute, elderly women, leading one journalist to comment wryly, "Anyone who speaks to Minnie Barton more than a minute and a half is bound to hear something about the needs of middle aged and older women who are poor and friendless in L.A." To partially meet this need, the camp in Sunland was transitioned into a home for these women, including Hilda Smith, who in 1938 celebrated her 98th birthday there.

In 1942 Minnie retired from the police force, but not from the fight. Now a beloved and much feted Los Angeles hero, she continued to fundraise constantly. The war years found her advocating parental responsibility and the right of social workers to inspect homes suspected of abuse, in spite of a "man's home being his castle." She also bewailed the fact that there were numerous missions caring for homeless men in downtown L.A., but not a single one for women.

Until the end, Minnie continued to be a fundamentally friendly, happy person. In 1943, the Soroptimist Club held a bean and salad dinner at the Minnie Barton Home. Now large and in charge, Minnie performed a deadpan song and dance routine in a skimpy costume, much to the delight of the audience. She kept her positive spirit till the end, dying after a long illness in July of 1946.

Into the Future

Fortunately, the dilapidated pile of stones in Griffith Park is not Minnie's true memorial. In 1952 the Big Sister's league opened a new home at 679 S. New Hampshire Street in Koreatown. In 1980, the League changed its name to Children's Institute International. Today CII provides clinical services, youth developmental programs ad parental counseling to over 20,000 at-risk Angelenos on three campuses, including the Koreatown location. They are currently building a fourth campus in the Watts neighborhood, an endeavor of which one assumes Minnie would heartily approve.

Hadley Meares is a writer, actress and singer who traded one Southland (her home state of North Carolina) for another. She favors the underbelly, the unexplored and the untamed. Naturally she is a regular at the Dresden, where she sings syrupy ballads as often as she can.

Top: Minnie Barton Memorial at Griffith Park. Photo by Hadley Meares.