One Hundred and Fifty Years On: African American Military Portraits from the American Civil War

There is currently a jewel of an exhibition at the California African American Museum (CAAM). Why a jewel? Because, though it is small, the more one looks at it, the more depths there are to see.

The exhibition, which was put together over three months using images downloaded from a Library of Congress collection, does at least two things very well indeed. In terms of race and class it describes a more complex picture of mid-nineteenth century America than is usually projected into the public realm, and it offers an example of what I'll call "publicness," in excellent operation.

"People tend to think that black soldiers were all escaped slaves," said Edward Garcia, the curator, designer, and primary fabricator and installer of African American Military Portraits from the American Civil War, "but these photographs represent a cross-section of American society. "

Take, for example, Private John Sharper's carte de visite. As with all of the exhibition's portraits it is reproduced twice: facsimiles of the small originals are mounted beside enlargements. In Private Sharper's case both prints depict a slim young man standing at attention in a military encampment. In the smaller of the two, he looks like a giant. Enlarged, his wide-apart eyes and sweet smile become visible. As does the photographer's stand that's keeping him still, and a painted backdrop of tents and cannon, the small scale of which causes him to loom.

A text explains that Private Sharper was born in New York and had been a printer before he enlisted in the 14th Rhode Island (Colored) Heavy Artillery Regiment at the age of twenty-two. As Ed Garcia pointed out, the trade of printer required not only education and a high degree of literacy, but also the capital (or inheritance) to get a business started.

With the vast majority of serving African Americans being enlisted men, an ambrotype of an unidentified "Union Army Officer" likely represents one of the rare few -- approximately 0.064% of an estimated 186,000 black soldiers -- who received a commission. Wearing a tailored jacket and "decidedly non-military" trousers, the unnamed man carries a weapon reserved exclusively for officers.

These men are middle class; perhaps even well to do. Their status was uncommon in a country where 7 out of every 8 African Americans were enslaved, but their images are tiny windows into something of the diversity of the mid-nineteenth century African American experience.

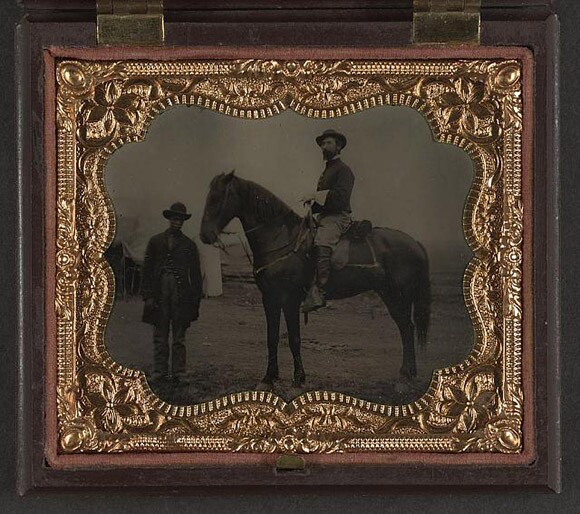

"Mounted Union Officer with Groom," in which a white man sits astride a horse while an African American groom stands at the animal's head, speaks to a more universal experience. The classic triangular composition, with the officer's head at the apex, makes a visual equation between height and superiority that diagrams the rider's power. A cliché of martial (and royal) portraiture, the equation is meant to reiterate and naturalize that power, along with the laws and customs by which it is maintained.

In a country in which the enslavement of African Americans was still legal, and where, until 1864, the "lowly" groom depicted here would have earned $3.00 (approximately 20%) less per month than his white comrades, this image represents a hierarchy of race and class. As the accompanying text explains: the "social hierarchy of the era is plainly evident. It was a time when the white officer class generally did not mix socially with the enlisted class...regardless of race."

The photographs, documents, and artifacts on display at CAAM reveal much about the role and conditions of not only African American Union soldiers, but also African Americans per se in the mid-nineteenth century. They demonstrate that, in a vicious context of legalized inequality and what a Museum didactic describes as the "racial prejudices common at the time," lives of great diversity were being lived.

Museums are repositories for artifacts and knowledge, and it is to be expected that they open up complex thought for public consumption. Thus, with this show, we could say that CAAM is just doing its job. But there is more to be said here, I think, about why this particular job is so important at this particular moment in time. It has to do with the popularity of Steven Spielberg's movie "Lincoln," which focuses on the President's efforts to achieve the slavery-abolishing Thirteenth Amendment. So much acclaim has this movie received for its historical accuracy, that it runs the risk of standing in much the same relationship to the American Civil War as Polanski's "Chinatown" does to L.A.'s water history.

In the context of contemporary education and popular media that do little to write African Americans into American history, let alone explore the diversity of African American experience, "Lincoln" begins well. It starts with a pre-battle conversation between the President and two African American soldiers, by which the significance of "Colored Regiments," and the discrimination faced by African American troops is established, before Corporal Ira Clarke (David Oyelowo) says:

"...now that white people have accustomed themselves to seeing Negro men with guns fighting on their behalf, and now that they can tolerate Negro soldiers getting equal pay. Maybe in a few years they can abide the idea of Negro lieutenants and captains. In fifty years, maybe a Negro colonel. In a hundred years, the vote."

Whether or not President Lincoln mingled with Union forces in this way, in terms of projecting a more-than-usually complex picture of mid-nineteenth century America into the public realm and positioning African American concerns in primary relationship to the conflict, this is great, right?

Well, yes. Except that rather than portend an ongoing recognition of African American centrality and experience, the scene stands alone. It is a devise by which the filmmaker describes the arena that Lincoln is about to enter in his fight for emancipation.

How could it be otherwise? "Lincoln" is not a documentary. It is an unabashed example of "the triumphalism of Great Man moviemaking." Focused on its hero journey, the movie necessarily drains agency and voice from everyone else in order to augment the status of the main man.

One might reasonably point out that the opening scene does use African American voices to describe the magnitude of the mountain that Lincoln is about to move, when it could as easily have used a conversation between, say, white anti-abolitionists.

Perhaps I should be grateful for that opening scene. But I cannot help but feel that opportunities were missed. Where amongst the movie's abolitionist protagonists is Frederick Douglass, the former slave, Lincoln advisor, and advocate for equal army pay who, as Michael Shank points out in a Washington Post article, "made this film scene possible"? And what of Elizabeth Keckley, another former slave and Mrs. Lincoln's dressmaker? Her limited role in the movie elides activism, which included founding the Contraband Relief Association, an important but largely forgotten aid organization made by and for former slaves and African American veterans.

Rather than live up to the promise of its opening scene therefore, "Lincoln's" nascent complexity is extinguished by the Great White Man juggernaut that scene introduces. To quote Professor Kate Masur: "It's disappointing that, in a movie devoted to explaining the abolition of slavery in the United States, African-American characters do almost nothing but passively wait for white men to liberate them."

A current FIDM exhibition of costumes from Oscar-nominated movies includes some of the Elizabeth Keckley-inspired dresses that Joanna Johnston designed for "Lincoln." Is it noteworthy that, while the "Lincoln" clothes are exhibited on pale linen-covered forms, the other garments are overwhelmingly displayed on glossy white mannequins? Or that a mannequin designed to resemble Jamie Foxx, which displays a costume he wore to play the eponymous ex-slave in Tarantino's antebellum rescue movie "Django Unchained," is painted high-gloss white?

Perhaps not, but it is surely noteworthy that, one hundred and fifty years after African Americans were finally allowed to enlist in the Union army, but at a 20% lower wage than their white comrades-in-arms, the wages of white men now exceed those of African American men by approximately 30%.

And it is likewise notable that institutional funding repeats, and even increases, that percentage difference. According to Guidestar, a fee-based service that aggregates the most recent publicly available financial reports from nonprofit organizations, in 2011 CAAM received less than 1% of its revenue from government grants, while such neighboring and comparable institutions as the Natural History Museum, the California Science Center, and the California Military Museum received, respectively: 1.8%, 23.9%, and 69.4% of their revenue from the same source. (Similar free data for 2010 is available here:NHM, CSC, CMM.) In other words, these three institutions received up to 39 times the relative governmental allocation made to CAAM.

This then is why CAAM's "African American Military Portraits from the American Civil War" is important: because while many things have changed since the Civil War, too much remains the same. Whatever our ethnicity, we all need the complexity and nuance that a public institution such as CAAM puts forth. It is a crucial counter to the aforementioned juggernaut, which profit-driven pop culture is unlikely to provide.

There is still time to see John Sharper and his comrades-in-arms in this rich exhibition that's been produced on a shoestring; it's open until April 14th. CAAM does not charge an entrance fee, but if you can, please give generously to the donation box at the door.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.