Grin and Bare It: The Street Politics of Smiling

There's an old home movie that my family likes to watch, given to us by a former neighbor who was up on the latest technology in 1964. In this silent black-and-white movie it is Easter Sunday, and all the kids on the block are gathered in the neighbor's backyard for an egg and candy hunt. My three older siblings, all of them under the age of 10, are among them. The day is bright and everyone is running around happily, sometimes waving at the camera or darting past its field of vision as they search for holiday grail.

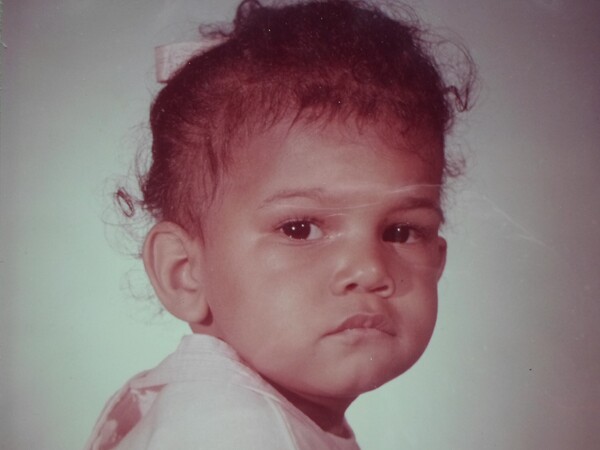

The camera pans over to the sliding glass door in front of the back porch where my mother is standing. She is dressed smartly, her hair done in a Jackie Kennedy-esque style. She is smiling. I am peering out from behind her, two years old and not smiling at all; in fact, I am glowering like I resent being there. My brow is furrowed and the shadows on my face cast by the bright sun intensify the bona fide frown. Even for a two-year-old not quite used to the world and occasions like this, I am a dramatic contrast to the gaiety around me. My mother tries to encourage me to look at the camera and lighten up, maybe join in the fun, though she doesn't try very hard. She seems used to it already.

My family always laughs aloud when they see this part of the movie. "Look at you!" they shout. "Not smiling, all put out, mouth all stuck out. You haven't changed at all."

Really? I think at first they are making fun of me, and I feel a surge of another, ancient resentment rooted in years of being a middle child -- what did any of them know about me, anyway? Then I realize they are right. I don't walk around with my mouth stuck out anymore, but I am not a serial smiler. I never have been. Maybe it was because I was timid -- I hated loud noises and loud, chaotic parties. Or maybe because I talked to myself and read a lot of books and thought a lot afterward about what I'd read.

But for whatever reason, a non-smile was my default expression, which personally never thought of as a frown, just as my face at rest. Neutral. But the rest of the world saw it as a kind of pathology that needed correcting. "What's wrong?" adults would ask me kindly, and kids would ask almost sneeringly. "You look so serious." When I got older, men on the street would chide me for looking so forbidding, marring what was to them an otherwise pleasant appearance. "Lighten up, girl!" they'd say by way of encouragement. "Things can't be all that bad." I always wanted to say back, oh yes they can. Sometimes they are. Instead I flashed a brief smile before relaxing back into my normal look, sometimes known as the look. This wasn't the most honest response, but it kept inquiring strangers at bay. For somebody who had no problem living in her own head -- as a reader and observer, later, a writer -- that was the goal.

The oppression underlying the directive for women to smile is the provocative subject of a traveling public art series, Stop Telling Women to Smile, by New York-based artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, who swung through downtown L.A. recently. I really get it. But as oppressive as the smile directive could be to girls (I don't recall boys being ordered to smile) I understood where it came from.

In the black community in which I grew up, smiling reflected an optimism and emotional fortitude that was spiritual armor that everybody -- kids, grownups, professionals --needed in order to be successful in the real world. Showing distress or even looking troubled was not something you wanted to do amongst white folks who were judging you unfavorably anyway; a smile radiated confidence that firmly refuted those judgments. A smile also had purpose and dignity, the modern antithesis of the old shuck-and-jive grin born of minstrelsy and other forms of mindless entertainment that was all meant to reinforce the racial status quo. What I was encouraged to adopt in the '60s and '70s was a post-Movement, I'm-black-and-I'm proud kind of smile that spoke to a new racial order in which I mapped my own fate, danced for nobody but myself. A smile lit from within, not demanded from without.

I agreed with all that sentiment, even as a somber-faced child. I still do. But I remain fairly hopeless at telegraphing contentedness and confidence when I don't actually feel it. Wearing a mask, however valid the need, is not my strong suit, which is probably why I studied acting (not writing) in grad school; I thought I needed to at least learn how. Except that what I really learned is that acting is not about wearing masks at all, but about taking them off. It's about being yourself. I don't recall anybody ever advising me to do that. I suspect that if somebody had, I might have smiled for real.