Managing Perceptions of the Occupy L.A. Raid: The Tyson Heder Trial

Editor's Note: Jason Rosencrantz is a downtown L.A. resident who last year became an active participant in Occupy Los Angeles and wrote commentary about the movement for KCET. The LAPD's eviction of occupiers at the park surrounding L.A. City Hall brought about numerous arrests, including that of Tyson Heder. Documenting a number of court cases was not just personal for Rosencrantz, but also about keeping a historical record, told through story.

On the night of the eviction of Occupy L.A., KCAL9 broadcast live footage of an increasingly violent confrontation between a videographer and a cluster of LAPD officers in tactical gear.

It was perhaps the most sensational interaction captured by the embedded press pool that night, and the incident stood in marked contrast to the after-action analysis proffered by LAPD Chief Beck and Mayor Villaraigosa -- that the eviction stood as an exemplary instance of "constitutional policing," characterized by restraint, professionalism, and an "absolutely minimal" use of force.

As if to consolidate this interpretation, the City Attorney's Office charged the videographer, Tyson Heder, with four counts of resisting arrest and two counts each of battery and assault. After almost a year of motions and deliberations, wherein the assault charges were eventually dropped, final verdicts on the other six charges -- including two counts of battery on a police officer in the form of "spitting" -- were reached last week in a trial presided over by Judge Yvette Verastegui in Department 6 of the East L.A. Courthouse.

Leading the prosecution was Deputy City Attorney Jennifer Waxler, a familiar face at Occupy L.A.-related trials, who called eight police officers to testify against Heder.

The Plan

The plan to evict Occupy L.A. had been developed over the previous month by a "planning cell" led by Sgt. Brian Morrison, the prosecution's first witness.

Sgt. Morrison described how he was deployed to Oakland on November 3rd in the wake of the evictions of Occupiers from Ogawa/Grant Plaza in order "to learn what happened" there and to prepare for an eviction of Occupy L.A. "once civic leaders decided."

Sgt. Morrison, a straight-arrow '50s throwback type who described himself as "in charge of the tactical eviction of the park" described the plan: 1100 tactical police and 300 support officers would be used, since the "best way" to "minimize force" is "to create an overwhelming force." The overall goal, explained Sgt. Morrison, would be "to prevent a disorderly egress."

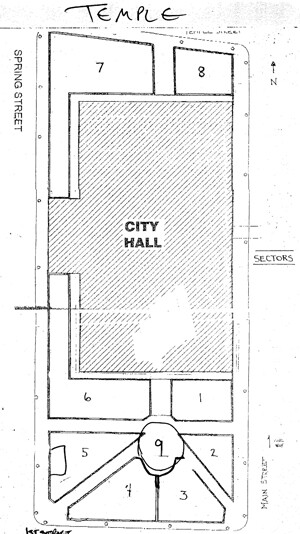

To accomplish this goal, the park would be broken into sectors, each consisting of an unpaved area that for months had been occupied by tents. These sectors were numbered clockwise around the center of the main lawn to the south, then up along the thin strip of lawn to the west, and finally to the north lawn of City Hall.

Teams of tactical police would move to establish skirmish lines around each sector, but the skirmish lines were to remain porous and allow people to leave until after the official dispersal order was given. After allowing a final chance to comply with the dispersal order, the skirmish lines would then be sealed and all who failed to leave would be arrested.

There was a last minute change, however, that would create some confusion. As the execution phase approached, the command staff became aware of a hole in their plans: the center paved area at the base of the south steps, where people had been accustomed to gather for General Assemblies, was being filled with people linking arms in solidarity and telegraphing their intention to stay.

In response, the area was designated as an additional sector. "Sector 9 was a late addition" created "about 15 minutes before the operation," explained Sgt. Morrison. It was on the stairs just above this ad hoc sector that the altercation between the LAPD and Tyson Heder took place.

First Contact

The first officer to make physical contact with Mr. Heder was Sergeant Rudy Barillas, a 15-year vet of the LAPD who delivered his testimony in a low and gravely monotone -- think Christian Bale's voice from under the Batman mask.

From the witness stand, Sgt. Barillas explained that his main objective was to help secure Sector 1, just to the west of the south stairs, and echoed Morrison's description of the overall plan: "people were going to be asked to leave, then arrested if non-compliant."

Sgt. Barillas recounted how he first saw Heder on the stairs as he was getting into position, but what exactly happened next was the subject of much controversy over the course of the trial -- and would ultimately prove decisive when it came time for the Jury to deliberate.

Under questioning from Waxler, Sgt. Barillas said it was his "intention" to get Heder off the stairs and direct him to one of the two media areas, either at the top or the bottom of the stairs.

This talk of "intention" initiated an awkward back and forth between Waxler and her witness as she struggled to get Sgt. Barillas to distinguish between his private intentions and his actual words and actions.

If that was your intention, asked Ms. Waxler, "what did you actually do?"

"I grabbed him in the elbow-bicep area," said Barillas. "And I tried to push him into Sector 1."

"But did you say anything?" asked Waxler.

Barillas, as if realizing what the prosecutor was looking for, finally recalled that he said, "come with me."

When asked how the defendant responded to being grabbed, Sgt. Barillas' stoic visage bubbled with emotion -- something like repressed rage: "He said, 'Fuck you! You haven't told me to leave! Fuck you!'"

The defendant then "held onto the railing," according to Sgt. Barillas, and continued to yell obscenities until "he spit on me... on the chin and chest area."

Under cross-examination by Mr. Heder's lawyer (also friend and surfing buddy) Joe Singleton, however, Sgt. Barillas qualified and reversed much of this testimony.

Sgt. Barillas admitted that he approached Mr. Heder from behind, hidden from view. Reviewing the video before the jury, he couldn't hear himself saying "come with me" at all -- though he could hear subtle atmospheric sounds such as footsteps on a tarp. Ultimately Sgt. Barillas admitted that he never announced his presence.

The video also showed that Mr. Heder did not use any profanity when first grabbed, contrary to Sgt. Barillas' earlier testimony.

He also conceded that Mr. Heder was standing outside of Sector 1, which was Barillas' primary objective to secure, and that he had no reason to expect that Mr. Heder wanted to bring harm to any officer.

Sgt. Barillas exhibited other inconsistencies as well. He initially reported to his colleagues that Mr. Heder "touched" him -- with no mention of "spitting." In fact, the spitting charge only appears in an "arrest supplemental report" drafted months later at the request of Sgt. Morrison, who oversaw the eviction operation.

Worse still, Sgt. Barillas couldn't decide upon when the alleged spitting took place. At one time testifying that the spitting happened as a result of the baton push and at another time testifying that the baton push happened as a result of the spitting.

Incidentally, according to Sgt. Barillas, the baton push had no causal connection to Mr. Heder falling down the stairs -- first Sgt. Barillas pushed the defendant with his baton, then the defendant "tripped on the tent."

Under Waxler's redirection, Sgt. Barillas explained that as a police officer he has the right to arrest someone without announcing himself if he has probable cause. Ms. Waxler, however, failed to get Sgt. Barillas to articulate what exactly that probable cause was -- and the question was left hanging in the air until closing arguments.

Much Evidence, Not Much Coherence

Other police witnesses had similar problems cobbling together a coherent story out of their police reports, the memories, and the video evidence.

Captain Incontro and Negative Space:

For example, Captain John Incontro, the top ranking officer on the south lawn that night, testified that he heard two officers ask Mr. Heder to leave the area before the incident occurred, and that by refusing to leave Mr. Heder was "obstructing officers from getting their work done."

But upon cross examination, Singleton got Incontro to testify that he did not personally witness the beginning of the incident, and that the video, contrary to his personal recollection, reveals no officers asking Mr. Heder to leave either before or after the beginning of the incident.

Redirecting, the Deputy City Attorney articulated a theme that she would return to again and again whenever police testimony seemed to conflict with video evidence. She argued -- in the form of questions to the witness -- that video "represents a limited perspective," and that the scene was noisy and often nothing can be heard over the defendant's yelling. Captain Incontro's testimony, therefore, "did not pertain to what was just on the video, but what was actually occurring that night."

Officer Vago and the First Takedown.

The testimony of Officer Thomas Vago was also problematic. Vago, an import from Harbor Division for the big event, was among those officers who joined in pressing their weight against Mr. Heder once he was taken to the ground. During the incident, Officer Vago distinguished himself by being the first to punch the defendant.

"I punched him in the right thigh, four or five times, to overcome his resistance and gain compliance." Such "distraction strikes" were necessary, he explained, in order to get Mr. Heder to unwrap the camera strap around his wrist, and then to cuff him and lead him to "safety."

Vago also had to reverse testimony that Mr. Heder was told to "let go of the strap," and countered earlier police testimony that Mr. Heder was kicking while they were trying to cuff him. Officer Vago, who was "bear hugging" Mr. Heder's legs at the time, testified that he never kicked.

Officers Medina and Barber and the Second Takedown

The most dramatic case of two police contradicting each other's testimony happened when first Officer Joshua Medina, and then his partner, Officer Barber, were called to the witness stand.

On this much they agreed: After being called to assist with cuffing the defendant, they were tasked with leading Heder away for processing. The field jail had been set up on Temple and Main, so they took the most direct route that night -- up the south stairs and through the interior of City Hall.

Once inside and just beyond reach of any embedded or independent media, Mr. Heder was for the second time that night tackled to the ground, accused of spitting, and punched -- this time in the face by Officer Medina.

Officer Medina, a five-year vet with a boyish face, who normally works gang enforcement detail in the 77th precinct, explained that Mr. Heder "got loose out of the flex cuffs." That's when he noticed a second metal cuff "dangling" from one of Mr. Heder's wrists. Since "a metallic cuff can be used as a weapon" they decide to "forcibly take him to the ground" into a "felony prone position," their knees once again pressed into Mr. Heder's back.

Mr. Heder was "still being aggressive and hostile towards us," and "trying to kick," accused Officer Medina. That's when Officer Medina notices "speckles of spit on my face-shield [and] formed the opinion that he spit on me." Then, when Mr. Heder "makes a facial expression, I thought he was going to spit on me again... [so] I punch him two times in the face and eye area."

On that much Officers Medina and Barber agreed, but they had very different recollections of what happened next.

Officer Medina recalled that he and his partner sat with the defendant "for 30-45 minutes," during which time Mr. Heder was "not moving much anymore." Then, after they regained their strength, they delivered the defendant through the building and out again to the field jail. In the last leg of the journey, Mr. Heder went limp in an act of passive resistance. They then returned to look for security cameras that might have captured their actions -- but found none.

But under oath Officer Barber testified that they held the defendant to the floor for just "seven or eight minutes" and that he and his partner never went back to look for security camera evidence.

Finally, Officer Medina's police report stated that four officers led Mr. Heder away for processing, not just he and his partner. But, no, "those two officers were not there," he explained. "That was the arrest of Danny Johnson."

Reasonable Use of Force

The prosecution's final witness was Sgt. James Katapodis, a 34-year LAPD vet now in charge of a LAPD leadership course adopted from Westpoint Military Academy.

Sgt. Katapodis was there as an expert on the use of force, and Waxler guided him though each instance -- Sgt. Barillas' baton push, Officer Vago's "distraction strikes," the takedown by officers Medina and Barbara as well as Medina's punches to Mr. Heder's face.

"Everything I saw was reasonable and consistent with what we teach at the Academy," declared Sgt. Katapodis.

In response, Singleton called David Dusenbury, a retired Long Beach Deputy Chief of Police with experience on review boards that took place in the wake of the Rodney King beating, to give competing expert testimony on the proper use of force.

"I saw no evidence that Mr. Heder committed any crime in any of the videos," noted Dusenbury. Moreover, the actions of Sgt. Barillas were "absolutely uncalled for" and "constituted misconduct," especially when "he pushed Mr. Heder down a flight of stairs" because of the "potential for substantial bodily damage."

Dusenbury thought that Sgt. Barillas' actions were "so egregious," in fact, that Captain Incontro should have "relieved him of duty" and then "initiated a complaint" against him.

Grabbing must come with instructions, explained Dusenbury, and police officers must identify themselves. Mr. Heder was reasonably "irate" after he was pushed down the stairs, but was "not a threat, other than coming up the stairs and demanding to know Sgt. Barillas' name."

What should Sgt. Barillas have done?

"He should have provided a name," said Dusenbury.

Furthermore, during the times when several police officers were kneeling their weight into Mr. Heder's back and neck area, there was a significant danger of "compression asphyxia" -- a situation where the lungs are unable to inhale after exhaling due to the pressure on his back.

Finally, Dusenbury questioned the competence of the team of police officers unable to cuff a single subject.

Tyson Heder's P.O.V.

After patiently and silently listening to so many police officers testify against him, Tyson Heder was finally called to the witness stand by his friend and lawyer to tell his side of the story.

Heder explained that he had never been to an Occupy event before, and wouldn't have been there on the night of the eviction if he hadn't been at the Redwood bar, just a few blocks away, shooting a local band for his website.

After the shoot, he noticed helicopters circling City Hall and, camera still charged, decided to investigate.

Focusing on the viewfinder of his CANON EOS 60D that he held at "chest level," Heder entered the park from 1st Street and into a "peaceful" and "casual" atmosphere he thought "felt like a street fair" or "public gathering."

Equipped with a wide-angle lens, he meandered through the crowd and up City Hall's south stairs in order to capture a wide shot of the unusual event.

As columns of police filed down the right and left sides of the staircase, a detail caught the videographer's eye -- a sign critical of the Mayor posted on the central handrail.

With an eye towards composition, he began to frame a shot of one of the police columns emerging from behind the sign. That is when "somebody grabbed [him] from behind."

"Don't touch me!" he yelled, repeatedly, until he is pushed with a police baton and tumbles down the stairs.

He never spit on anyone, he claimed, either before or after being pushed down the stairs.

Jumping back up, he yelled "Dickhead, what is your name?"

"I'm not schooled in this," he mused, "but I know enough to find out the person's name who assaults you. I would have filled out a report or found the appropriate steps."

Then things moved quickly. At the same time as being told to put his hands on his head, he felt hands on his neck and back -- "that's when the swarm begins."

He didn't pull away from anyone, he says, but officers grabbed him from different directions, sending everyone into a "spiral."

"In my subconscious is my camera," recalled Heder, "a $900 piece of equipment that I didn't get easily... I was trying to protect my camera, so I didn't break my fall with my hands," he says. Reliving the takedown, the 35-year-old's calm demeanor breaks with emotion, and takes a moment to fight back tears. "Excuse me," he said before continuing on.

At the bottom of the dog pile, he remembers being confused and that his thought process was reduced to a single directive: "just hold onto the camera... it's the only record of what happened to me."

He testified that ne never resisted, but merely tried to breathe, that his arms were behind his back, that he was being hit, and that he was confused and, above all, scared.

After being led away up the stairs and into City Hall, he recalls stumbling and being pulled into the building. "My first sensation was my face against the cold marble floor," he said, again taking a moment to fight back tears.

Inside City Hall, as he was being punched in the face, he remembers thinking "'I got my camera, I got my camera" before slipping into unconsciousness.

Deputy City Attorney Waxler's cross exam consisted of taking Mr. Heder once again through the series of videos, step by step, trying unsuccessfully to catch him is a contradiction or admit to failing to respond to a command.

"I was not resisting," he says regarding the dog pile. "The only movement I did was to keep my head from being crushed to the ground."

"My hands were behind my back," he says after being asked why he didn't give up his hands. "They were given up as much as they could be... All I wanted to do was get air in my lungs and hold onto my camera."

Probable Cause

Ultimately, Sgt. Morrison's testimony describing the grand plan would set the stage for the Singleton's closing argument. The overarching goal of the plan, "to prevent a disorderly egress," obviously entails that the police allow an orderly egress, but the last-minute addition of Sector 9 complicated things by effectively sealing the natural exit route from the south steps.

But Mr. Heder was never even asked to leave, even as Sgt. Barillas himself begrudgingly admitted. And because Mr. Heder was given no instructions, the question of Heder's guilt regarding all the resistance charges brought against him largely hinged upon whether Barillas had probable cause to arrest him.

That he was violating park hours was a non-starter, since these had not been enforced for two months, and there were literally hundreds of other people in the park at that time not being arrested. In any case, the LAPD's own eviction plan called for allowing people to leave the park until after the official dispersal order, which wasn't delivered by Officer Orlando Nieves until Mr. Heder had already been pushed, tackled, and punched. The City Attorney's office never even bothered to charge Mr. Heder with violating park hours.

So what was the probable cause to arrest? On pain of absurdity, it couldn't be for resisting arrest itself.

Much of Waxler's case rested upon Mr. Heder "failing to obey commands," so she scoured the videos for instances when police can be heard communicating to Mr. Heder.

In the case of Captain Incontro, for example, there were two such instances. The first was a "come hither" motion he made with his white-gloved hand.

"I am trying to get him to come to us so that we can arrest him without injury," he explains. "My plan was to get him to submit to an arrest."

When Heder fails to respond to that subtle gesture, Incontro told the defendant to "put his hands on his head." But Sgt. Barillas testified that Mr. Heder had "less than a second" to respond before his hands were grabbed and taken to the ground.

Verdict and Post Trial

In the end, Tyson Heder was cleared of all the charges brought against him.

The Jury came back from deliberation with unanimous "not guilty" verdicts on 4 of the 6 charges, and since the majority of the Jury leaned "not guilty" on the remaining 2 charges, they were ultimately dismissed.

After the verdict, and the jury were free to discuss the case; they gathered in the hallway with the lawyers from both sides for post trial analysis.

Overwhelmingly, they said they considered Sgt. Barillas' testimony to be "inconsistent" and "unbelievable," and that, generally speaking, it was "conflicting testimony" on the part of the police that undermined the prosecutor's case.

The fact that the arrest of Mr. Heder seemed to be unlawful from the beginning inclined the majority of the jurors to dismiss all subsequent charges leveled against him.

The only question on which the juror's disagreed was whether Mr. Heder's alleged act of passive resistance -- lifting his legs and going limp when, after being pushed and tackled and beaten, he was finally carried to the detention van -- constituted "resisting" Officers Medina and Barber.

One juror went as far as to compare the spitting charges to comedian Dave Chappelle's joke about "sprinkling crack" on victims of police brutality.

In a victorious mood, Mr. Singleton indicated his next move: "I plan to sue the LAPD and the city of Los Angeles for violating Mr. Heder's Constitutional rights."

Managing Perceptions

I wondered why the City Attorney's office chose to so aggressively charge and prosecute the battered videographer, especially in the light of recent news about the budget office's proposed cuts to the City Attorney's staff. How much does a two-week trial, especially one with so many police witnesses, cost the city? The city's chief prosecutor, the politically ambitious but recently frustrated Carmen Trutanich, has a well-known history for aggressively targeting political activists -- perhaps he confused the explicitly non-activist videographer for an agitator.

In her opening argument, Deputy City Attorney Waxler claimed that there were only "two types" of people in the park that night -- those "there to protest against the 1%" and those whose only goal was "to rally against the police." Heder's "aggressive behavior" clearly put him in the latter category, so the police "had to react" while using "as little and as reasonable force as was necessary."

I asked Waxler whether she or someone else in the City Attorney's Office was responsible for choosing to prosecute Mr. Heder for these charges, and also what her reaction to the verdict was.

To both questions she responded with "no comment."

I suppose it could be a matter of perception -- what one person sees as a disoriented videographer struggling for breath, another sees as a criminal resisting arrest. Sgt. Scott Stevens, another officer called to testify (in the video, he was the one yelling "Stop resisting!"), thought that it was "obvious from the video" that Mr. Heder was "not being beaten," and Ms. Waxler in her closing arguments told the jury that they "can see how the defendant is resisting."

Perhaps the perception of Mr. Heder as a dangerous criminal has something to do with the fear that police feel for the public they are meant to serve. Captain Incontro, for example, spoke of his concern about "pockets of darkness" and the possibility of people "in the trees" throwing urine and feces at his officers -- as if they were entering a range of wild monkeys. At least two officers commented on the defendant's physical size, as if a few extra inches or pounds would give Heder an unfair advantage against the overwhelming force put together by the LAPD command staff.

The management of perception is a dominant theme for the entire incident. Sgt. Morrison had a "plan for credentialed media" that would "grant access" to an exclusive media pool made up of establishment organizations that are, in my opinion, fearful, dismissive, and jealous of citizen journalism.

These establishment sources trade deference to power for access, such as when broadcasters from KCAL9 -- part of the LAPD-vetted media pool -- freely admitted to censoring its own skycam footage to "protect the integrity of the police action."

Captain Incontro talked about the media relations officers whose job it was to "direct" the media pool, and Sgt. Barillas "noticed he didn't have credentials" before pushing Mr. Heder with down the stairs with his baton.

Another telling moment was Captain Intontro's very different handling of embedded press, even when they got in the way of police operations. Captain Incontro testified that the KCAL9 cameraman's mounted light was a "safety issue" and was "interfering" with his officers as they wrestled with Mr. Heder -- but there was no question of arresting the embedded cameraman, much less tackling him to the ground and punching him in the face.

In the end, the Jury members did not perceive that Tyson Heder was guilty of anything, though it might have gone differently if his own video footage had not survived to be shown in court. But one can detect in Heder's trial a warning to unembedded perspectives on major police actions. Independent journalists, beware! Not only do you risk being tackled and beaten and jailed, you may also spend the better part of a year defending yourself against trumped up charges brought against you by the City Attorney's Office.