No Backup: The Lessons of Christopher Dorner

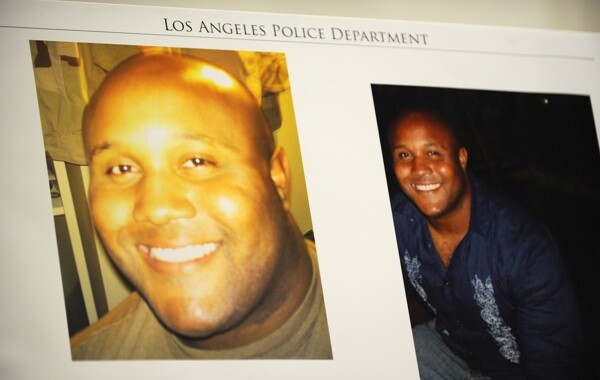

This being Valentine's Day, I was figuring on writing something about love. But local events in the last week have intervened big time. So in the aftermath of the manic Christopher Dorner manhunt (an aftermath that isn't yet official, as of this writing) it feels appropriate to talk about not love, but something related: idealism.

I'm sure many more details will emerge in the coming days and months about Dorner, about what exactly prompted his ill-fated mission of revenge against the LAPD, about the veracity of his exhaustive manifesto. But the information we do have is more than enough to have fueled lots of empathy, especially from black Angelenos, for Dorner's personal battle against a police department that he experienced firsthand as racist and corrupt. When Dorner concludes in his manifesto that the department has culturally changed little since the nadir days of Rodney King and Rampart, it's not hard to get

"amens" from people of color who've been disproportionately targeted and profiled by the LAPD since its inception. Department reforms notwithstanding, nobody African-American that I know has the warm and fuzzies for police officers today. To say things have gotten better is only to say that black civilians and motorists are unfairly treated, say, fifty percent of the time as opposed to all the time. An improvement, but not cause for celebration or letting up on suspicion. Far from it.

What makes Dorner's grievances so compelling, of course, was that he was a cop. He was an insider. And an insider with a mission; an idealist, he saw himself bettering the LAPD by being conscientious, by making himself a model for the kind of compassionate attitudes and behavior the department said it wanted to adopt. In a bigger sense, he wanted to uproot the institutional racism that in many black people's minds is synonymous with the LAPD and with law enforcement in general. He saw himself as heroic that way.

But when the institution prevailed and Dorner got fired -- unfairly, the evidence so far suggests -- he spiraled into a sense of defeatedness, anger, and helplessness that ultimately led to another, more destructive and clearly un-humanistic mission that has so far eclipsed any discussion about root causes or unsexy things like institutional oppression.

But what's most interesting to me and to folks I've talked to is that Dorner, like so many of us who've been obstructed by racism and racist attitudes in our lives, was angry; unlike most of us, he snapped. In other words, Dorner's personal reaction to what he saw as a systemic problem was highly unusual. Most black people file away their disappointment over not getting a job, over being called names or being told, subtly or otherwise, that they are not equal. It's a survival thing honed over hundreds of years, an act of self-repression and resilience that's practically become part of black culture. Dorner refused to be quiet or file away his feelings, not just because he was young and fed up but because as a police officer with the duty of protecting and serving, it seemed like he felt he had some responsibility to speak up. He had to let us know. That feels heroic.

But it's too bad he felt he had to speak up in such a terrible way -- the manifesto alone would have sufficed. Being a black martyr and going up against the system and then down in a blaze of gunfire, or in just a blaze, turns out to be so much "Django Unchained" spaghetti-western hooey. Idealism can be dangerous, depressing, the source of your undoing, especially if you're black. I suspect that we'll be learning the lessons of Dorner for many Valentine's Days to come.