What the Great Migration from The South to South Central Meant to Some

My father turned 80 last week. It's a startling number; it feels like the real break from middle to old age, the point at which people officially start considering you fortunate to be alive at all. I know that longevity is increasing, that making it to 100 is becoming more and more common. But those are trends, statistics.

In real life, the fact that my father is 80 is nothing short of triumphant because so many men in his family didn't make it to that age. They didn't even come close. My father's father died of a heart attack at 52, and my father's oldest brother died the same way at nearly the same age. Congenital heart disease, cigarette smoking, and stress all figured into it; of my father's seven brothers, only one lived to 80. Last week, my father became the second. He was the youngest brother and is one of the very few of his generation still living. The last brother died in 2001, just after the turn of the new millennium.

My father has kind of joked about his good luck, and his solitude, over the years. Once the baby and the political rebel of the family -- he was a full-fleged '60s activist -- he is now its patriarch. That shift has made him more willing to talk about the past, which I always knew generally but not in great detail until the last decade or so. What I always knew is that he moved to L.A. from New Orleans in 1942 when he was nine, that he graduated from Fremont High School in 1950 after being one of the first blacks to go there, that he went into the Air Force as a musician, that he worked at the post office and got married and had kids and eventually earned a degree from UCLA in 1959.

The facts of his life were always whirlwind, something recalled often but as a kind of checklist that he never seemed eager to examine in any great depth. Of course, that was common to people in his family, and my mother's family, too, the lack of sentiment about the emotional details of their lives and what it all meant.

I realized later that people were too busy trying to invent those lives as they moved from the South to California. After being generations in New Orleans and Louisiana, Los Angeles became a starting point for not living on the margins for once. The relative absence, or the inconsistency, of Jim Crow in L.A. in the '30s and '40s wasn't without hardship, but it was a beginning of a new existence, of finally feeling American. Really, what was the point of looking back?

Not that the South was forgotten. When I was growing up, adults talked with great animation about New Orleans and the seventh ward where practically all of them were born. The Creole community was incredibly tightknit. But it was clear to me that they were done with it, that I would get no romantic stories about how things were so much better for us back there and back then. They made it clear that while New Orleans would always be a touchstone and a defining experience in a way that L.A. would never be, neither was it home in the fullest sense of the word. If it had been, they would not have left it so completely.

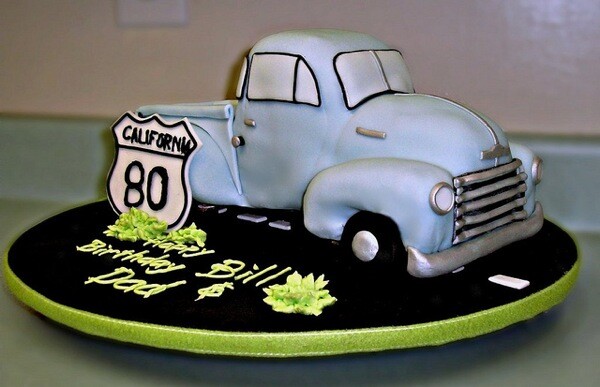

We had a little party for my father over the weekend, the first time we'd ever celebrated his birthday with anything other than the immediate family gathering around a cake at the dining room table at my parents' house. This year we had some extended family members and friends over, and food under a pergola in the backyard. The weather was warm and breezy, vintage L.A. My father was relaxed and expansive, even happy. He had made it to 80. It all felt like home.