LA Rent Relief is Coming. But as Immigration Raids Continue, It Might Not Close the Gap

This article was first published by the nonprofit newsroom LA Public Press on December 9, 2025 and is republished here with permission.

Los Angeles street vendor Maria Luz said she’s making about half as much money selling pupusas as she did before federal immigration raids escalated earlier this year. At a downtown rally hosted by the LA Tenants Union last week to put pressure on county supervisors to pass an eviction moratorium, the vendor said she’s struggling to pay her rent of around $1,200, but is also afraid of going to work.

“I’m worried that if I go in the street, I’m risking that immigration will grab me,” Maria Luz, who requested her first and middle name be used due to safety concerns, said in Spanish.

If there were an eviction moratorium, she said, “ we can work in peace.”

LA County Supervisors have taken some action to help renters affected by the federal government’s immigration crackdown. In September, the Board directed staff to put together a $30 million rent relief program. A month later, the Board declared a local emergency over federal immigration actions, a precursor to passing an eviction moratorium for tenants affected by the raids. But they have stopped short of passing the moratorium, which housing advocates say would keep people in their homes.

Isaiah Feldman-Schwartz, a tenant lawyer with Los Angeles for Community Law and Action, called a time-limited eviction moratorium “ the simplest and most effective way to keep people from being evicted.”

Over the last several years, the Board of Supervisors took action within days or weeks to enact temporary eviction moratoriums to address the COVID-19 and January’ wildfires. They have yet to take similar action in response to the ICE raids, which have been happening for six months. Thousands of tenants are still at risk of being arrested, indefinitely detained and deported. Many immigrants have lost income because they are afraid to leave their homes. A July study from UC Merced found a 7% decrease in noncitizen workers reporting to their jobs in June.

In September, researchers from the Rent Brigade published a survey of 120 immigrant renters and found that their average weekly wages dropped by 62% since the raids started. By August, a little under one-third owed more than one month’s rent, making them vulnerable to eviction. The survey also cited a USC study from last year that found 67% of the county’s 280,000 undocumented immigrants in 2021 were rent-burdened, or paying more than 30% of their income towards rent.

LA Tenants Union organizer David Albright characterized the effects of the ICE raids as a series of “compounding economic crises,” where restaurants, small businesses and street vendors are losing business, and people are afraid to go to work. “ This is a city-wide issue,” Albright said. “And it affects all of us.”

Albright was skeptical that the county’s rent relief program would be enough to help. “This $30 million is nowhere near covering the number of people facing eviction in LA County right now,” he said.

LA Public Press reached out to all five County Supervisors. Each one responded with statements supporting and defending the rent relief program.

Rent relief application opens next week, but concerns

The county’s rent relief application will open at 9 a.m on Wednesday, Dec. 17. Only landlords can directly apply, although tenants can refer their landlords to the application. They will have until 4:59 p.m. Jan. 23 to apply for rent relief, according to Keven Chavez, spokesperson for the LA County Department of Consumer and Business Affairs. Chavez said priority would be given to small landlords who own up to four housing units and property owners and tenant households with incomes at or below 80% of area median income. Priority would also be given to high-need communities determined using the county’s Equity Explorer map.

Chavez said the application should take half an hour to fill out and that the county could finish reviewing applications and make a decision within 30 days. Applicants would have access to a 24/7 portal with updates from the Department of Consumer and Business Affairs. A customer service phone line will also be available for the program.

According to the Board of Supervisors’ rent relief motion, relief will be capped at six months of rent not to exceed $15,000 per unit.

But organizers like Albright are still concerned about whether the program will meaningfully help tenants. He chalked up the new program to a “bailout for landlords,” since they’re the ones allowed to apply directly.

Kyle Nelson, director of research and policy for tenant rights at Strategic Actions for a Just Economy, is also concerned about only allowing landlords to apply, pointing out that they could refuse to do so. “Having a tenant’s entire sense of housing stability dependent on whether or not a landlord is going to cooperate and sign up for rental assistance just seems like a terrible idea,” he said.

Nelson and Feldman-Schwartz said the rent relief program doesn’t seem to include an affirmative defense for tenants fighting their eviction in court if their landlords refuse to apply for the program, or a tenant who has a pending application.

“If evictions can proceed while applications are pending, eventually landlords just run out of patience and they’re like, ‘Show me the money, or you’re out,’” Feldman-Schwartz said. “Having some way for a judge to recognize that there’s a pending application, and that the tenant shouldn’t be evicted … I think that would be helpful as well.”

Chavez did not address whether a rent relief application could be used as an affirmative defense in court but told LA Public Press that landlords would become ineligible for relief if the county learned that they applied but also pursued an eviction for that same time period. The county “would pursue all available avenues” to recover funds for any relief granted and would reach out to the landlord “to discuss the benefits of rent relief and the drawbacks of pursuing an eviction in hopes of a resolution that is both positive for the landlord and the tenant.”

Albright also said that he was concerned that the program would require tenants to disclose their immigration status to landlords, “who we kind of all know in this equation, is potentially someone who might retaliate by calling ICE.”

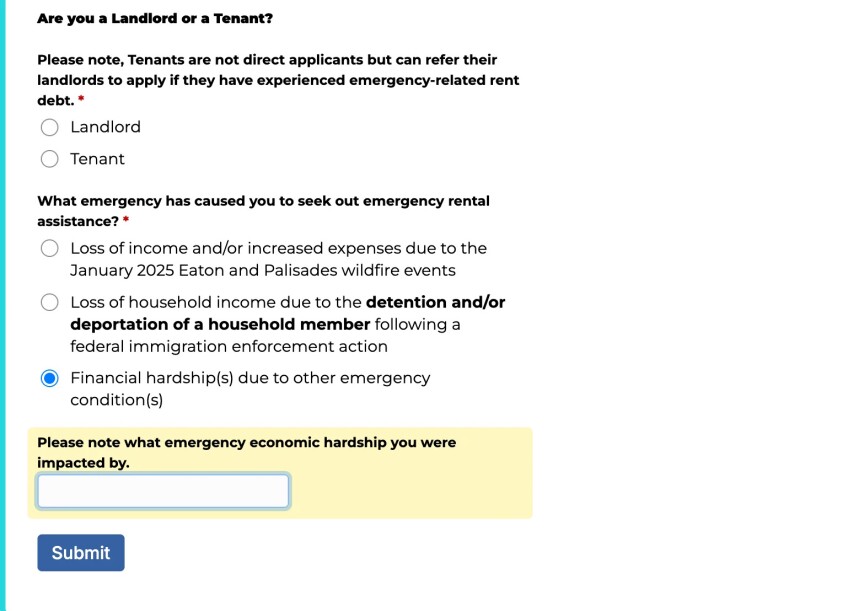

Chavez told LA Public Press that tenants would not have to certify their immigration status with landlords to apply for rent relief. But an interest form people can fill out notifying them of when the application opens does have a required multiple choice question asking for the reason a potential applicant is interested in the program. One option is loss of income due to detention or deportation of a household member related to immigration enforcement. The other options relate to economic impact from the 2025 LA wildfires and “financial hardship(s) due to other emergency condition(s).” People who select that latter option are prompted to specify the hardship.

Daniel Yukelson, executive director of the Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles, said in response to tenant fears that their landlord would ask for their immigration and report them to ICE, “Even the most inexperienced landlord knows that doing so is a violation of California’s discrimination laws, and for that reason, it’s just not happening.”

In July, LA Public Press found that while landlords were prohibited from revealing their tenants’ immigration status, in practice, a tenant might not be able to raise that issue in court if they were already detained or deported.

LA Public Press contacted all five County supervisors asking for comment on the issues housing advocates and experts have raised. Both Supervisors Kathyrn Barger and Lindsey Horvath disagreed with the idea that the rent relief program was a “bailout for landlords.”

“Rent relief is a homelessness-prevention tool that helps both tenants and small property owners remain stable,” Barger said in a written statement, adding that the program was designed to “prevent fraud and ensure landlords who receive funds meet their obligations.”

Barger’s colleagues also expressed confidence that the rent relief program would help immigrant tenants stay housed and that tenants would be protected from eviction if their landlords accepted funds. Supervisor Janice Hahn said the program would protect tenants from having to disclose their immigration status.

Some of the supervisors pushed back against an eviction moratorium. Supervisor Holly Mitchell said she was concerned tenants would be “saddled with an even larger bill that they can’t pay once the moratorium is lifted,” and was looking forward to getting more details about the moratorium once available. Supervisor Lindsey Horvath said the immigrant rights advocates she has worked with wanted to prioritize rent relief, but didn’t specify which advocates she was referring to.

Advocates argue an eviction moratorium gives more options to tenants who can’t pay rent

An eviction moratorium won’t stop landlords from filing evictions. Only the state’s judicial council, which oversees California’s courts, can actually ban evictions, whether the council does so on its own or the state legislature directs them to, according to Nelson. What these eviction protections would do, according to experts and housing advocates, is provide tenants with a defense in court if their landlord tried to evict them.

An eviction moratorium would allow tenants to certify that immigration enforcement has prevented them from paying rent on time, similar to COVID-19 eviction protections and the six-month moratorium this year for tenants impacted by the LA wildfires.

There are limits to an eviction moratorium. At an Oct. 7 board meeting, assistant county counsel Peter Bollinger said his office found that eviction moratoriums have been upheld in court because they were adopted in response to a declared emergency and “relief was temporary and narrowly tailored to address the impacts of the emergency.” In 2021, the city of LA’s pandemic eviction moratorium was upheld for this reason.

Bollinger said that the eviction moratorium would also have to preserve landlords’ due process rights to challenge a tenant’s assertion that they are unable to pay rent because of immigration enforcement. This means tenants would have to give landlords notice of this claim. Supervisor Janice Hahn said during the meeting that she was concerned that the county would put tenants in a “vulnerable position” if they had to disclose their immigration status.

A memo drafted by lawyers working on behalf of the LA Tenants Union recommended that tenants should only be required to tell their landlord that they are unable to pay the rent, without detailing why. “This would allow the law to be tailored to fit the current emergency, while not putting vulnerable families at further risk due to requirements that they identify themselves as immigrants.”

Along with outlining the efficacy of an eviction moratorium in the memo, the lawyer recommended alternatives, such as raising the allowable rent debt threshold that tenants need to incur before being evicted, as well as a ban on no fault evictions during the local emergency.

Last week, protestors’ message to LA supervisors was clear: Renters need protections today. “Not tomorrow.”

Jose, a small business owner at Santee Alley, said business revenue for him and others in the area is down significantly. The once bustling downtown marketplace has been hit hard by both the January wildfires and the ongoing immigration raids. Jose, who requested that only his first name be used for safety reasons, said he’s worried about making ends meet to pay his residential and commercial rents. “ We have two rents. And so we need a moratorium. We need help,” he said.

Rally-goers eventually entered the room where supervisors were meeting, chanting and holding signs saying “¡¡¡Evict ICE not us!!!” In response, the supervisors called a recess and left the room.