These LA Volunteers are Fighting Back by Documenting What Happens Inside Immigration Courts

This article was first published by the nonprofit newsroom LA Public Press on November 13, 2025 and is republished here with permission.

Isabelle is a legal assistant who has worked at several law firms and is interested in immigration law. Earlier this year, a summer associate from UCLA law school told her about a Court Watch LA training to prepare volunteers to observe hearings at immigration courts in LA County. Isabelle, who only wanted her first name used to protect her work, said she took the training on July 10 and has since attempted to observe seven or eight hearings at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center.

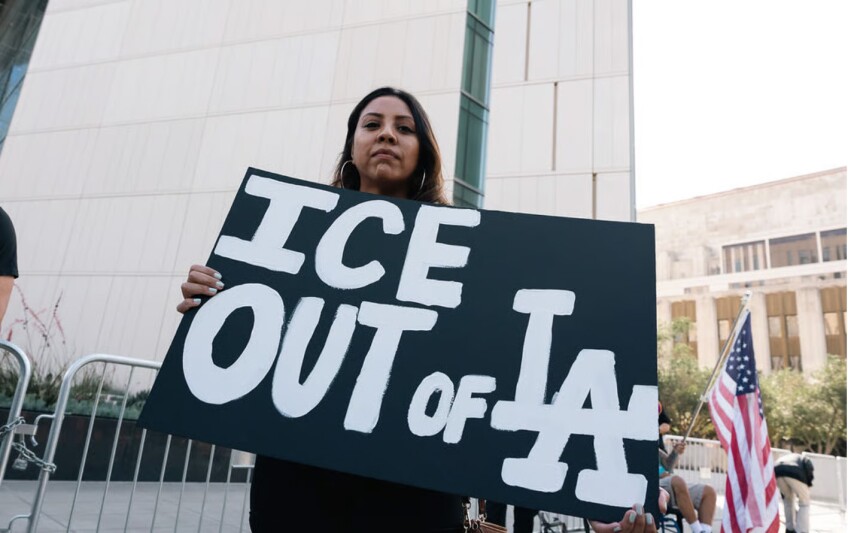

Court Watch LA has been training volunteers to observe immigration hearings for about five months. The program is aimed at tracking how court officials treat immigrants and their cases in immigration court. Like community members who record ICE agents during arrests, Court Watch LA volunteers are fighting back by documenting what they’re seeing — and making sure that the immigration apparatus doesn’t operate in darkness.

In her first months of volunteering and working as a legal assistant during ICE’s increased activity in LA County, Isabelle said she’s already observed things she found troubling.

She said she hasn’t always been able to get into the hearings she’s attempted to observe. On two occasions, she said a judge who presides over a courtroom at Adelanto Immigration Court did not let her in. On a third occasion, he asked who she was. When she identified herself as a court observer, she said he kicked her out of the hearing. “He was like, ‘I don’t know if any of the people here consent to you being here’ basically,” she said.

When she has been let in, Isabelle said she noticed that the court-provided interpreters translate what the judge is saying — but not necessarily what a person’s attorney is saying.

On one occasion, Isabelle said, a Spanish-speaking client had no idea of her fate, simply for lack of translation.

“She [mistakenly] thought she was getting deported at the end of the hearing because she was only hearing what the judge had to say,” Isabelle said, adding that the judge stopped her from explaining what she missed. “She left in tears and we weren’t allowed to speak to her.” Isabelle later confirmed to LA Public Press that the woman was not deported that day.

Court Watch volunteers submit their observations to a database, where Court Watch tracks potential due process violations in the immigration court system. Administrators also hope that understanding trends can inform their advocacy on behalf of immigrants being targeted by the federal government.

Sophia Wrench, a staff attorney at Public Counsel, also participated in Court Watch training and has since brought law clerks to observe immigration hearings. Public Counsel is also a Court Watch partner. Wrench believes that a court observer’s presence alone is important in the case. “ You are signaling to the judge that there are people watching and that they should act accordingly,” she said.

“ When we go in, we shine a light, our eyes help to visibilize what they’re trying to invisibilize,” Titilayo Rasaki told volunteers during a July 10 training. Rasaki is a policy and campaign strategist for La Defensa, a criminal justice reform non-profit that administers the program. The purpose, she said is to “ document the patterns of abuse and injustice that we’re seeing.”

Karen Garcia, a communications specialist with La Defensa, said the group has started noticing some trends: judges refusing to allow observers to attend some immigration hearings, language access issues (in one case, she said a translator spoke a different Farsi dialect than a defendant and in another case, she said there was no Spanish interpretation available for most of the hearing and so a defendant didn’t know that he was denied bond) and procedural hurdles. In one instance, she said an attorney tried to designate a country of deportation for their client, only for the court to assign another country.

Different rules in immigration courts

Volunteers with Court Watch say they’ve been surprised by the rules in immigration court, which can be different from the more familiar rules of criminal courts. For example, any type of hearing is typically open to the public in a criminal court. But in immigration court, only the master calendar hearings, which govern the logistics of a person’s immigration case, are open to the public.

A schedule of criminal court hearings is also often easier to find on the web. “We know a month in advance who’s being scheduled, what date, and what court, and what judge,” said Yesenia Samano, a Court Watch volunteer. For the immigration courts, Samano said she would have to do more digging to find out when hearings are taking place. At the July Court Watch training, volunteers were instructed to ask the clerk at an immigration courthouse of any master calendar hearings taking place that day or to find a judge’s WebEx link so volunteers can attend hearings virtually. These hearings tend to start around 8 am and 1 pm.

Similar to criminal courts, immigration court hearing rules can be strict. Volunteers are advised to only take notes with pen and paper in the courtroom, as not every judge allows laptops or other electronics into the courtroom. Volunteers are also advised to turn off cell phones completely before entering a courtroom. Samano said she’s even been advised to dress more professionally when going to the immigration courts.

Evidence of an immigration system overrun with new arrests

As both a volunteer and as part of her job, Isabelle said she observed a lot of differences at Adelanto since the escalation of federal immigration raids in LA in June. She said the volume of people in the detention center is higher, and it’s harder to get ahold of them.

“ When we try to schedule unmonitored calls, sometimes their voicemail is full. And I think it’s because there are so many people in there, they’re at full capacity,” Isabelle said.

The population is also different — more people are being detained who wouldn’t have been in the past.

“Either because they had a work permit and had a pending asylum application, or because they never had a criminal record or anything like that. People like that are getting taken [now],” she said.

Samano, who has also been observing criminal courts, has even seen evidence of the immigration crackdown show up in those courts. Last October, she was observing a court hearing at the Edward Roybal federal court in Little Tokyo, when suddenly, she said, officials brought in a dozen or more people who were chained up together. Some were in what appeared to be prison jumpsuits, she said, but most were wearing civilian clothes.

One of the chained men was brought before the judge for entering the U.S. illegally. “That was literally his only crime,” she said.

Samano said she wasn’t expecting to see immigration cases that day. “ I was shocked. Emotionally I wasn’t ready for that,” she said.

How to become a court observer

Anyone can walk into a courtroom and observe master calendar hearings at immigration court. But if you’re interested in learning best practices for becoming a court observer, you can keep an eye out for training sessions with La Defensa. The organization will start them up again in 2026.

Volunteers are encouraged to find and attend hearings and send their observations through the Court Watch LA portal through the end of the year. Next year, according to Rasaki, La Defensa and their Court Watch partners are hoping to expand their program capacity to support volunteers to accompany immigrants to their hearings and check-ins if they request it.

Volunteers should also assess their own risk when going to these courthouses, especially depending on their own immigration status. Public Counsel staff attorney Sophia Wrench advised people to not go to hearings in person if they’re afraid of being targeted by federal officials. She also suggested limiting personal conversations to outside of the courthouse. She added that people should not intervene if they observe ICE activity, because they could incur federal criminal charges.

Wrench did encourage people to participate in Court Watch if they could. Even if they do observe on their own, Wrench recommended collaborating with a group of people as well.

“If you’re taking notes as your own person, it’s helpful to be able to send that back to a group that can collect those notes and then do the analysis of what the trends are over time,” she said, adding that a group can cover more hearings and then process them together, “because it can be quite traumatizing to witness.”